|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

TCHS 4O 2000 [4o's nonsense] alvinny [2] - csq - edchong jenming - joseph - law meepok - mingqi - pea pengkian [2] - qwergopot - woof xinghao - zhengyu HCJC 01S60 [understated sixzero] andy - edwin - jack jiaqi - peter - rex serena SAF 21SA khenghui - jiaming - jinrui [2] ritchie - vicknesh - zhenhao Others Lwei [2] - shaowei - website links - Alien Loves Predator BloggerSG Cute Overload! Cyanide and Happiness Daily Bunny Hamleto Hattrick Magic: The Gathering The Onion The Order of the Stick Perry Bible Fellowship PvP Online Soccernet Sluggy Freelance The Students' Sketchpad Talk Rock Talking Cock.com Tom the Dancing Bug Wikipedia Wulffmorgenthaler |

|

bert's blog v1.21 Powered by glolg Programmed with Perl 5.6.1 on Apache/1.3.27 (Red Hat Linux) best viewed at 1024 x 768 resolution on Internet Explorer 6.0+ or Mozilla Firefox 1.5+ entry views: 2697 today's page views: 962 (23 mobile) all-time page views: 3733006 most viewed entry: 18739 views most commented entry: 14 comments number of entries: 1256 page created Fri Mar 6, 2026 15:42:21 |

|

- tagcloud - academics [70] art [8] changelog [49] current events [36] cute stuff [12] gaming [11] music [8] outings [16] philosophy [10] poetry [4] programming [15] rants [5] reviews [8] sport [37] travel [19] work [3] miscellaneous [75] |

|

- category tags - academics art changelog current events cute stuff gaming miscellaneous music outings philosophy poetry programming rants reviews sport travel work tags in total: 386 |

| ||

|

- philosophy - In resuming the discussion on Scott Adams' God's Debris (Here's Part One), it may be instructive to consider some readers' comments from the book's Amazon customer review page. As is usual, the glowing, five-star feedbacks gushing over the work in question are not as interesting as the put-downs. Some were evidently penned in a hurry: "From my reading experience was made of the following 20% stuff I already knew 70% interesting but useless, and thus I ignored it 30% really useful information that I will write down and review many times" Maybe there's some category overlap going on there. Some sniffed at Adams' perceived pretensions: "The only thing I can really say is that this book is absolute garbage. It's borderline plagarism [sic] (here, let me steal the writing style from Plato and move on), except that none of the ideas presented in this book make any sense when compared to the Republic..."

Plato is NOT amused. Um, so it's a dialogue. True that. Then again Plato likely adapted the form from earlier poets, and if this were to be considered plagiarism the libraries of the world would contain one comedy, one tragedy, one biography... you get the idea. I admit God's Debris isn't going to be challenging the Republic in philosophical canon anytime soon, though. "And I thought it couldn't get worse than the Dilbert cartoons, but this is worse. Much worse." Same reader that gave the last quote. Evidently not a fan. "...Otherwise, the ancient wise man comes across as an enthusiastic but naive youth. A "man who knows everything" would always include the Michelson-Morley experiment in an explanation of Special Relativity, and be numerate enough to avoid statements like "if you flip a coin often enough, eventually it will come up heads a thousand times in a row" (The odds of 1,000 consecutive heads is 1/2^1000 =~ 1/10^301. If every person presently alive on earth flipped a trillion coins a second until all conventional matter has vanished from the universe (10^124 sec), the chance of one person getting 1,000 heads in a row is still worse than 1:10^270!)" I'm not too well-versed in the intricacies of the M&M experiment, but if Einstein himself could use "When a man sits with a pretty girl for an hour, it seems like a minute. But let him sit on a hot stove for a minute and it's longer than any hour. That's relativity." as an introduction, that's enough for me.

"Ma'am, would you give me a minute?" (Source) The objection to the coin flip assertion is kind of strange, though. The reader appealed to practical considerations in rebutting a wholly theoretical statement, albeit with an appeal to the currently predicted lifespan of the Universe. From a mathematical point of view, though, for any finite X, the probability of a coin coming up heads X times in a row is definitely calculable, and in fact the statement that "if you flip a coin often enough, eventually it will come up heads (some gargantuan number) times in a row, (some gargantuan number) of times" is perfectly valid. This reminded me of an article in which a professor described one of his students as a whiz at numbers, who could solve extremely complex problems, but who steadfastedly refused to consider that numbers could have more digits than were displayed on his calculator. Quite a large blind spot maybe, but happily one that may well be overlooked in some specialties; Perhaps most people have some such "blind spots" of their own... Adams' challenge to "figure out what's wrong" received its fair share of attention: "For the record here are some of Avatar's errors of fact: (p19) magnetic fields can't be blocked; (p19) gravity propogates [sic] instantly; (p22) we don't understand how electricity travels; (p61) there is no friction between the Earth and the Moon (the statements about gravity and the Moon are wrong in multiple ways); (p66) the theory of evolution is a "concept with no practical application." A bit of research suggests that in fact, magnetic fields can't be blocked with non-magnetic materials, with a possible exception. As for gravity propagating instantly, I can't detect the Avatar actually implying "instantly" on page nineteen - but at least that's a fact. As for not understanding how electricity travels, it is true that we can explain - up to a point - electricity. We can talk about charge, about ions, electrons, conductors; But up to a certain depth, even the best scientists begin to hem and haw. If you asked, "what is fire", you would get responses about "chemical reactions", "oxidation" and the like, but what it is... well, suppose we change the topic? This may be to a degree an issue with language itself, with concepts being built on others - i.e. a Pegasus is a winged horse; I have seen wings, and I have seen a horse, so I can imagine a Pegasus. This may lead to circular references, which could be expensive - cue a man who once sought legal advice, and was told that he should prepare a will, because "if you die without a will, you would die intestate." Curious, he went home and picked up a dictionary, and lo and behold, under the entry for intestate: Dying without a will. Back to the novella: Page 34. "The human brain is a delusion generator. The delusions are fueled by arrogance - the arrogance that humans are the center of the world, that we alone are endowed with the magical properties of souls and morality and free will and love. We presume that an omnipotent God has a unique interest in our progress while providing all the rest of creation for our playground. We believe that God - because he thinks the same way we do - must be more interested in our lives than in the rocks and trees and plants and animals..." "...Practicality rules our perceptions. To survive, our tiny brains need to tame the blizzard of information that threatens to overwhelm us. Our perceptions are wondrously flexible, transforming our worldview automatically and continuously until we find safe harbour in a comfortable delusion." "...It is absurd to define God as omnipotent and then burden Him with our own myopic view of the significance of human beings..." This is something I always thought was kind of strange. Once, when we were two years old, we may have reckoned ourselves as obviously the most important thing there is and ever was. Most people grow out of that as individuals, but in their own societal groups, humans by and large retain a certain chauvinism, a subconscious validation that "we" are the centerpiece of Creation. The least bit of rational thought would reveal, as stated earlier in the novella, that joining the "right" religion is at best a slightly better than one-in-three chance, and at worst nearly impossible. How? So people usually gravitate towards religions their family or friends are in, figuring that even if it sinks, at least they're all in the same boat (a pleasant gesture); But in the same way that teens fooling around don't really think they'll be the ones to get saddled with a kid or some icky disease, that smokers regard lung cancer as something that "happens to other people", that investors assume that there will always be a greater fool to offload onto, it appears a congenital defect that we rate ourselves as somehow, special, and that our religion cannot possibly be a false one. Unbelievers and infidels are, almost by definition, the other people.

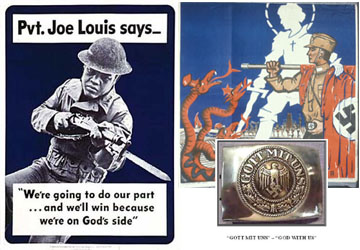

In foxholes, all think that the Big Guy's on their side (USA and Nazi WW2 propaganda) The desire towards good, towards virtue, is the most noble of passions; 孟子认为人性本善,荀子认为人性本恶, and i lean towards 孟子. But, as the ancient Greeks questioned, "Is what is moral commanded by God because it is moral, or is it moral because it is commanded by God?" The apparent dilemma is that if deeds are commanded by God because they are moral, then men need not tarry by worshipping, but concentrate on living a moral life, since morality and virtue are independent of belief; If deeds are moral because they are commanded by God, then if his will be to kill, then murder would be good (cue Abraham and Issac). As the example of the posters above illustrate, morality has little bearing on the invocation of the Divine - mere obedience without independent thought, harnessed by the malevolent, is the cruelest possible mockery of our innate desire towards good. Here, a slight complication arises: There are many widely accepted interpretations of God available in this world, and many of them are, how shall I put it, rather unfriendly to other interpretations. So in this admirable quest, a usual outcome is that one is introduced to the God(s) of one's loved ones, and quite often I believe this is the end of the story; Of course, this is not always the case, and sometimes we see within a family a colourful sprinkling of faiths, and behold Christians, Buddhists, Taoists, etc coexisting peacefully under one roof. Now, this is all well and good, but what do we have? In many religions, the adherents are admonished to "have no other Gods before Me", or some version thereof, with the implicit (or explicit) claim that all other religions are falsehoods. Now, a gentle believer might be sorely troubled, at his or her loved ones not following the one True way; This is not helped by a very sincere insistence of the extremely unpleasant consequences in the hereafter of not joining the correct religion, which is to say, the speaker's. Then again, this is perhaps to be expected. Let us imagine a scenario: A seeker after God approaches a holy man. "Guru, what do you believe?" Guru: "Oh, I believe in ..." Seeker: "Ah, so yours is the only way to God?" Guru: "No, there are many Ways to Him." Seeker: "I see." (Moves on) Seeker to Guru 2: "Guru 2, is yours the only way to God?" Guru 2 (with utmost conviction): "Yea, my son. Mine is the one, the only, the highest, the holiest God. If you do not believe in Him, you will burn for all Eternity, but fear not! Just accept Him, and you drink the milk of Paradise!" No contest there. This was recognized by the French philosopher Blaise Pascal, who proposed a rational gambit: Believe in God, and (your particular conception of) God exists: Infinite reward in the afterlife. Believe in God, and God does not exists: No gain, no loss. Do not believe in God, and God exists: OUCH! Do not believe in God, and God does not exists: No gain, no loss. Again, this is complicated by the inconvenient existence of multiple possible visions of God, but somehow I imagine that the true God would be rather unimpressed - there seems to be a poetic justice to Him turning his back on those who seek Him for reward. Richard Carrier pushes the case for God desiring honest skepticism and abhorring blind faith, in his The End of Pascal's Wager: Only Nontheists Go to Heaven: "It is a common belief that only the morally good should populate heaven, and this is a reasonable belief, widely defended by theists of many varieties. Suppose there is a god who is watching us and choosing which souls of the deceased to bring to heaven, and this god really does want only the morally good to populate heaven. He will probably select from only those who made a significant and responsible effort to discover the truth. For all others are untrustworthy, being cognitively or morally inferior, or both. They will also be less likely ever to discover and commit to true beliefs about right and wrong. That is, if they have a significant and trustworthy concern for doing right and avoiding wrong, it follows necessarily that they must have a significant and trustworthy concern for knowing right and wrong. Since this knowledge requires knowledge about many fundamental facts of the universe (such as whether there is a god), it follows necessarily that such people must have a significant and trustworthy concern for always seeking out, testing, and confirming that their beliefs about such things are probably correct. Therefore, only such people can be sufficiently moral and trustworthy to deserve a place in heaven--unless god wishes to fill heaven with the morally lazy, irresponsible, or untrustworthy. But only two groups fit this description: intellectually committed but critical theists, and intellectually committed but critical nontheists (which means both atheists and agnostics, though more specifically secular humanists, in the most basic sense). Both groups have a significant and trustworthy concern for always seeking out, testing, and confirming that their beliefs about god (for example) are probably correct, so that their beliefs about right and wrong will probably be correct. No other groups can claim this. If anyone is sincerely interested in doing right and wrong, they must be sincerely interested in whether certain claims are true, including "God exists," and must treat this matter with as much responsibility and concern as any other moral question. And the only two kinds of people who do this are those theists and nontheists who devote their lives to examining the facts and determining whether they are right." How convincing this argument is, I leave the reader to decide; But I would venture that the very last thing an omnipotent Godhead wants is for people to carry his balls (though this may not sound so implausible to people who do like their balls carried...) To be continued again... Next: Ten Years Ago This Day

|

|||||||

Copyright © 2006-2026 GLYS. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||