|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

TCHS 4O 2000 [4o's nonsense] alvinny [2] - csq - edchong jenming - joseph - law meepok - mingqi - pea pengkian [2] - qwergopot - woof xinghao - zhengyu HCJC 01S60 [understated sixzero] andy - edwin - jack jiaqi - peter - rex serena SAF 21SA khenghui - jiaming - jinrui [2] ritchie - vicknesh - zhenhao Others Lwei [2] - shaowei - website links - Alien Loves Predator BloggerSG Cute Overload! Cyanide and Happiness Daily Bunny Hamleto Hattrick Magic: The Gathering The Onion The Order of the Stick Perry Bible Fellowship PvP Online Soccernet Sluggy Freelance The Students' Sketchpad Talk Rock Talking Cock.com Tom the Dancing Bug Wikipedia Wulffmorgenthaler |

|

bert's blog v1.21 Powered by glolg Programmed with Perl 5.6.1 on Apache/1.3.27 (Red Hat Linux) best viewed at 1024 x 768 resolution on Internet Explorer 6.0+ or Mozilla Firefox 1.5+ entry views: 1688 today's page views: 449 (16 mobile) all-time page views: 3386490 most viewed entry: 18739 views most commented entry: 14 comments number of entries: 1226 page created Fri Jun 20, 2025 10:11:02 |

|

- tagcloud - academics [70] art [8] changelog [49] current events [36] cute stuff [12] gaming [11] music [8] outings [16] philosophy [10] poetry [4] programming [15] rants [5] reviews [8] sport [37] travel [19] work [3] miscellaneous [75] |

|

- category tags - academics art changelog current events cute stuff gaming miscellaneous music outings philosophy poetry programming rants reviews sport travel work tags in total: 386 |

| ||

|

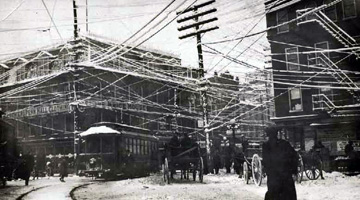

and will happen again." - Lefèvre channels Ecclesiastes. (and later the widow's mite) Quick read of the week's Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, freely available online due to its copyright having lapsed - it was first published in 1923. Anyhow, it's more or less an autobiography of legendary stock trader Jesse Lauriston Livermore, and being regarded as a classic, there is no shortage of commentary online, so I'll try and offer something slightly fresh, given my background. So, who was Livermore (Livingston in the book)? He was a self-man made in the truest sense of the word, born 1877, who was several times a multimillionaire (topping out at somewhere between a billion and 14 billion of today's dollars, depending on how the conversion is done). That said, he did himself in at 63, due to depression at having "only" US$5 million left, so the old adage about happiness holds. Keeping in mind that the book may not be a completely accurate account of Livermore, what we have is a kid from Massachusetts who got a job as a quote boy at a brokerage to escape the humdrum life of a farmer, and discovering that his talent for numbers had practical application; hours of staring at prices eventually granted him the ability to predict their movements - "seven out of ten cases", in his own words. A friend introduced him to the world of "bucket shops", where punters could bet on these fluctuations, and Livermore soon cleaned them out.  Not the cheeriest of places (Source: livermoresecret.com) At this point, we note that what Livermore did was mostly pattern recognition: "...after studying every fluctuation of the day in an active stock I would conclude that it was behaving as it always did before it broke eight or ten points. Well, I would jot down the stock and the price on Monday, and remembering past performances I would write down what it ought to do on Tuesday and Wednesday. Later I would check up with actual transcriptions from the tape." Well, one can argue that empirical science (i.e. science) is just pattern confirmation, but those were apparently less methodical times. The modern-day parallel would be hardcore technical analysts who swear by princples such as Elliott waves, Ichimoku clouds, MACD indicators and what have you, with the main distinction being that Livermore undeniably succeeded, perhaps helped by being ahead of his time. [N.B. Someone has gotten around to trying to predict Bitcoin prices using a neural network (which, the heavens know, has been tried often enough). Fair warning, it hasn't been that reliable, and some detractors have made the observation that it (and technical analysis in general) can be self-fufilling if enough people buy into it (just like the market itself, then)] How the bucket shops worked was, you "bought" stocks as per normal (but with a hefty commission), and with the additional handicap of being automatically wiped out if the stock ever dropped below some margin close to the buying price. Being pure derivative side-bets, however, the shops' transactions were not reflected on the actual market. Due to this, one could recognize that the shop operators had an incentive to manipulate the real market prices to break their customers' positions - and to add insult to injury, using the customers' own stakes. Of course, that's what they did. Despite all this, a twenty year-old Livermore still managed to earn US$10000, cueing his mom to tell him to sock it away, as moms are wont to do. He did indeed then lose three-quarters of it from the bucket shops' machinations, though he takes some relish in describing how the shops were beaten at their own rigged game by an even bigger fish. Eventually, he was banned from all his hometown shops, and left for New York to seek his next fortune - only to go broke. This wasn't that big of an issue since he would just borrow some capital to make it back from the local shops (who promptly banned him in succession), but it took several such cycles for him to realise that his finely-honed senses were not suited to actual trading. The stock exchange worked by submitting bids to the clerks - but by the time these bids were executed, the price could (and often) have moved (he obliquely hints that the brokers might have been executing trades in an order that suits their own interests) In this context, Livermore could be seen as a natural high-frequency trader (waiting for Flash Boys to come available at the library...), and indeed he takes on three custom exchanges (essentially higher-class bucket shops) by running direct wires to their brokers, mimicking how modern-day speed freaks colocate for that additional edge.  There were a lot of them (Source: retronaut.com) [Trivia: Up until 2005, trading on the NYSE was limited to the 1366 seat-holders, which were commonly family affairs. Apparently, the business wasn't very mentally intensive, and in the words of a former member, a none-too-bright Ivy League legacy kid could rake in an annual half a million in today's dollars mostly by being present, hence the good-natured welcome taunt: "Too dumb to be a doctor or a lawyer, his old man bought him a seat."] We get another memorable quote here: "There is only one side to the stock market; and it is not the bull side or the bear side, but the right side." (sorta-paraphrased by a WP candidate). This modest line hides much wisdom - one could question why falling stock prices should be associated with gloom, when the presence of short-selling allows bets in both directions? Or, if you're despondent when the price falls, you were doing it wrong in the first place. Livermore was, if nothing, a learner, and above that a practitioner - he tested his methods, and the sole criterion used was whether they made money. He didn't forget to jibe at on-paper traders either, comparing them to gunslingers who can snap the stem of a wineglass at twenty paces, only to forget that in a real duel, the wineglasses shoot back. He also takes pains to warn that speculation is more than just math, and technical overspecialization can be crippling, anticipating Taleb's example of a pure correlation-based trader earning millions over years, only to lose it all and more besides in days when the World War threw all those connections into disarray (he did live this trope himself too) - then immediately cautions against being a semisucker who knows just enough to harm himself. To this end, he introduces the wise old Mr. Patridge: "...when you are as old as I am and you've been through as many booms and panics as I have, you'll know that to lose your position is something nobody can afford." The "position" referred to here being his stock assets in a bull market, said in response to a youngster who advised him to sell before buying back later in anticipation of a temporary dip. Mr. Patridge's point was simple - the big money was not to be made by such fluctuations, but in the overarching trend. Sure, being clever on spotting minor moves can be satisfying, but evidence indeed bears out that active traders generally lose, largely due to the fees involved. Which brings us Livermore's key advice: buy near the start of a bull market, sit tight, sell completely near its end, and don't try to get the exact tops and bottoms - "One of the most helpful things that anybody can learn is to give up trying to catch the last eighth or the first. These two are the most expensive eighths in the world. They have cost stock traders, in the aggregate, enough millions of dollars to build a concrete highway across the continent.". The next chapter describes him selling whilst on holiday, merely on a hunch, right before the Great San Francisco earthquake, which brought him US$250000 (news travelled more slowly then; he would much later stress the importance of experience in cultivating intuition, over mere mathematical facility). However, the true lesson here would be to trust oneself - previously, Livermore had derided stock players as by and large eager to be led to do things, so that they can blame the leader on failure (as H.L. Ham noted)  To some: devastation. To others: profit (Source: conservation.ca.gov) That said, he promptly went broke again, after correctly predicting a bear market, by selling short too soon (slow news bites both ways), and then earned it back by instigating the selloff of a counter (i.e. dumping), before avoiding the big crash of 1907 (the one that J.P. Morgan was hailed as containing by underwriting the entire system) upon the failure of one of his pet theories - that the rise of a stock price over a psychological milestone should ordinarily confer it the momentum to surge somewhat further. Here, Livermore insists that he is not primarily concerned about the money - but about being right about the market. Previously, he had described a bucket shop owner as being less annoyed at having to pay out, than being fooled by him. Which makes sense, since these men were probably already some distance from playing for survival. He then goes on to double down his teaching on not trying to over-time the market (in more contemporary parlance, "catching a falling knife"), but only to get in once a clear trend emerges. He proceeded to make a killing on commodities (which Keynes managed too, but no less than Sir Issac Newton himself imploded at), to the extent that newspapers headlines had him as cornering the monthly cotton market (recall, he was just thirty), which was a break for him given that he actually had no idea what to do with all that cotton. Anyhow, this got him on the radar of a new acquaintance, who as it turned out was a kindred spirit in relishing being right - "You wouldn't get enough fun out of it... you are not in Wall Street because you like easy money." However, it was a saleman who managed to somehow foist a set of rare books on him, before agreeing to rescind the deal for two hundred bucks and letting on that he did Morgan in the same way. And went on to take Livermore's friend for two thousand bucks. Some men can, indeed, sell anything to anyone. Livermore then went on to lose his cotton fortune by trusting his partner, selling winners and buying losers, before spending more trying to shore up the losers. Then followed an episode in which he was hired effectively as a smokescreen, in which he resented owing a debt of gratitude - for, as he says, money can be paid easily, but not favours, and the incident kept him from being his own man for some years. He emerged from that into a lean market, in which opportunities simply didn't exist (or so he says, but he's the expert), and wound up owing over a million dollars. Interestingly, his major creditors were all encouraging of him declaring bankruptcy, just so he could get back into the right frame of mind. Relieved, he called in one last favour for a trading line of five hundred shares, and waited six whole weeks to commit what could otherwise have been his last plunge. The market went into full swing, and he admitted that at these times, all that was needed to make money was simply to be inside. That got him three million, and he went on to repay all his original debts - last of them all the whiner who had badgered him for a mere eight hundred. Next was setting up some untouchable trusts for his family, which as history informs us, was a smart precaution. Well, Livermore's next commodity win, after a rocky start, was in coffee, after which the president of a tin company attempted to influence him by slipping a tip to his wife; that backfired spectacularly, as Livermore sold instead, having already determined that it was a bear market. He proceeds to repeat his disdain for the common investor, who will leap on tips happily, but switch off if an attempt to explain the reasoning behind the advice is offered, capping it with an anecdote about a floor trader who had lost big on a tip due to insider dealing - but was game for more tips from the same. Another story: a savvy investor heard a rumour about one of his portfolio companies being mismanaged, and paid a personal visit to the president, who was completely convincing in his usage of figures to rebut those accusations. Nevertheless, the investor sold all his shares, and was proven right. His reason? In making his case, the president went through sheets of unnecessarily expensive paper with nary a thought - an example of see what they do, not what they say. Next up was his piece on manipulation, beginning with his observation that the big guys all loved trying to corner some market or other, which actually often didn't make financial sense - he put it down to ego. For himself, he was contented with merely "pumping" stock up a couple of times, by arranging it such that the biggest holders kept their part in escrow, before initiating a move up by buying. This was of course the signal that chart-watchers loved, and the ruse generally worked. Livermore gave himself a pass by mentioning that the underlying stock did have real value. What can we say about this character? He was, certainly, shrewd, an appellation he applied liberally to others. More than that, however, very many of the general ideas he laid out, are near truisms today. Yet, despite winding up with a substantial packet by any means, he was by all accounts desperately unhappy - if only because he saw no way to buy back in. Perhaps, for him, the game was all there was. Next: Spend Spend Spend

Trackback by automaty do kawy

Trackback by Total Hair Regowth Review

Trackback by จำนองบ้าน

|

||||||||||||||

Copyright © 2006-2025 GLYS. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||