|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

TCHS 4O 2000 [4o's nonsense] alvinny [2] - csq - edchong jenming - joseph - law meepok - mingqi - pea pengkian [2] - qwergopot - woof xinghao - zhengyu HCJC 01S60 [understated sixzero] andy - edwin - jack jiaqi - peter - rex serena SAF 21SA khenghui - jiaming - jinrui [2] ritchie - vicknesh - zhenhao Others Lwei [2] - shaowei - website links - Alien Loves Predator BloggerSG Cute Overload! Cyanide and Happiness Daily Bunny Hamleto Hattrick Magic: The Gathering The Onion The Order of the Stick Perry Bible Fellowship PvP Online Soccernet Sluggy Freelance The Students' Sketchpad Talk Rock Talking Cock.com Tom the Dancing Bug Wikipedia Wulffmorgenthaler |

|

bert's blog v1.21 Powered by glolg Programmed with Perl 5.6.1 on Apache/1.3.27 (Red Hat Linux) best viewed at 1024 x 768 resolution on Internet Explorer 6.0+ or Mozilla Firefox 1.5+ entry views: 2398 today's page views: 525 (110 mobile) all-time page views: 3400510 most viewed entry: 18739 views most commented entry: 14 comments number of entries: 1228 page created Sat Jul 12, 2025 19:09:49 |

|

- tagcloud - academics [70] art [8] changelog [49] current events [36] cute stuff [12] gaming [11] music [8] outings [16] philosophy [10] poetry [4] programming [15] rants [5] reviews [8] sport [37] travel [19] work [3] miscellaneous [75] |

|

- category tags - academics art changelog current events cute stuff gaming miscellaneous music outings philosophy poetry programming rants reviews sport travel work tags in total: 386 |

| ||

|

- current events - As the USA subprime mortgage crisis deepens, this may be a good time to attempt my own simple common-sense economical interpretation of it, with as few clunky terms as possible. Here goes nothing:

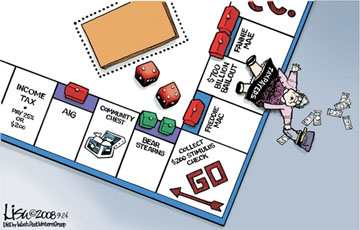

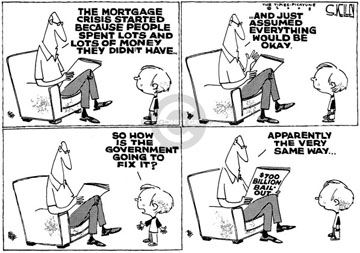

Now, some foundational economics. Let's say a guy wants to borrow money. If he doesn't want to bother friends and relatives, he will have to go to some commercial moneylender, such as a bank. These moneylenders want to make money too, of course, and they will assess how likely he is to be able to pay them back - note that the very act of trying to get a loan is a sign that one is not exactly flush with cash! If the guy has a job with a steady income, has demonstrated financial discipline by managing a credit card or two well, has collateral to put up etc, these will be considered positive indicators, and he will be able to borrow more and have to pay less for the privilege of borrowing, in general. Then what about people without those good attributes? Indeed, they may be even more likely to need money, but are also more likely to be rejected outright, thus the refrain "banks only want to lend you money when you don't really need it". Luckily (or unluckily) for them, there's another approach which uses the same concept as in insurance, which is risk pooling - Let's say 1000 high-risk characters want to borrow $1000 each, and experience tells a bank officer that only half of them will be able to pay it back. In this case, the officer can charge a borrowing fee of something over $1000, and still turn a profit. In short, it doesn't matter if individual borrowers default, if the return on all of them as a group is sufficient. Obviously, the higher the borrowing fee, the less likely a borrower desperate enough to accept it, and with a poor enough reputation not to get better terms, will actually be able to repay his debt, so the risk/return evaluation probably can go only up to a certain rate in reality. Loansharks understand this, and that's why their repayment rates are that outrageous - they expect a lot of their clients to run road to JB, and the spray paint and pigs' heads aren't going to pay for themselves. This is not to say lending money to supposedly high-risk entities is always bad - microfinancing small projects in developing countries has brought a lot of good, and the initial rationale behind "junk" bonds of providing credit to promising but unknown companies was good too. The key point is that the risk involved has to be well managed. In microfinance, community pressure to repay reduces risk. For "junk" bonds, the companies should be investigated to ensure that they have a sound business plan and actually have a decent shot at making it. The problem comes when the lender doesn't much care about the risk, or just tries to make it up by insisting on a higher return. Again drawing on the loanshark parallel, doubling the interest weekly is meaningless if the debtor is completely penniless. To some extent, this was what happened in the USA. Lenders got too greedy in accepting loans, since they would earn commissions doing so, or earn in other ways by "repackaging" these loans in complicated ways, and while the housing market was doing well nobody wanted to ask too many questions - why not just profit instead (Stick figure illustration)? Financial institutions ended up granting worse loans than they should have, and unsurprisingly the returns were lower than they should be. Same as in most bubbles. This became a big problem since just about every major institution was involved in this colossal miscalculation. But wait! Since some of these institutions (e.g. the mortgage lenders Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae) were considered "too big to fail", as their bankruptcy would likely lead to a chain reaction as other institutions with close links would also fall and so on and so on, the USA government had to bail them out by subsidizing them (i.e. pumping money into them).  (Source: Cartoonist Group) However, just bailing financial institutions out in essence says, "Go on and take risks with the money. If you get lucky, you are a hero and keep all the profits. If the worst happens, everybody including the common taxpayer who had nothing to do with your institution, will pay the costs for you." Or as former American president Andrew Jackson put it so eloquently in the early 19th century: "Gentlemen, I have had men watching you for a long time and I am convinced that you have used the funds of the bank to speculate in the breadstuffs of the country. When you won, you divided the profits amongst you, and when you lost, you charged it to the bank. You tell me that if I take the deposits from the bank and annul its charter, I shall ruin ten thousand families. That may be true, gentlemen, but that is your sin! Should I let you go on, you will ruin fifty thousand families, and that would be my sin! You are a den of vipers and thieves." Though of course in the end the government had to swallow principles, and "reward" incompetence and greed, which could be understood as a non-credible threat in game theory: Government to Big Institution: Don't take funny risks, or we won't help save you. Big Institution: Yeah right, both of us know that you have to, or we all go belly up. Government: Darn, you're right. *Big Institution takes funny risks* Where's the accountability now?  (Source: Cartoonist Group) I gather that the root of much sadness in this world is the desire to consume more than one deserves (i.e. worked for). It must be acknowledged though that "what one deserves" is difficult to quantify in an increasingly knowledge-based economy. A fisherman in the past could for example haul in a basketful of fish in a day, and exchange it for a stool that the carpenter next door made that day. While obviously this does not address whether ability should be factored in (i.e. if the carpenter improved his skill such that he made two stools in a day, should he then give both for the same basketful of fish?), at least the products were tangible, and all parties could understand what they are haggling over. This does not hold up as well in the symbolic world of today, though. What's the real value of a programmer, a research scientist, or an accountant? Whatever they can get in a free market is of course one answer, and often the only one available. The troubling thing is when obtaining value from short-term speculation, essentially trying to get something from nothing, becomes more popular than actual productivity, and people struggle mightily over a few microscopic bits on a bank's harddisk drive instead of doing stuff that actually helps other people. Financial intelligence needs to be backed up by some basic foundations, but this is unlikely to come into widespread effect spontaneously due to "selfish" individual motivations. The good news is that this won't be the end of the world, and once again it will ironically be time for those who kept clear of the initial bubble to buy into newly-undervalued properties at bargain prices, and sell sometime into the next bubble. And the system continues... A slightly more in-depth summary can be found on Investopedia. Having said that, the effects are already being felt locally, as the DBS High Notes 5 meltdown reflects. Predictably, many investors are claiming that the product was misrepresented, and that they didn't understand the risks involved, which could well be the case given that bank relationship managers will likely be eager to push these risky products if they can earn higher commissions on them. Therefore, without knowing in detail what the recommendations were, nobody can comment properly on this issue. (It may be that the featured investor's complaint that "...we were told this was a low-risk investment" actually referred to a "low ten percent risk only of losing everything!", who knows?). To be sure, bank instruments aren't simple to digest - try to understand what this (random) fund actually does, and the risks involved, from its "factsheet". I doubt the average retiree has a good idea what half the numbers mean. It seems common sense for soon-to-be retirees who want to plunge the majority of their savings into a single investment to be sure that their capital is protected. One (modified) piece of advice from Get Rich Slow by Tama McAleese sticks in my mind: The first thing that one should ask when buying a bank instrument is, how much will I be guaranteed to get if I invest in it, and what are the chances that I will lose my investment (McAleese also recommends getting a signed statement from the bank manager, but I doubt this applies as much in Singapore unless one has a ton of money)? Any chance above zero percent is probably too much for a lot of people, but if, knowing that, they still plunk all their savings into it... really it must be their own fault - for if all goes well and they earn higher returns than normal, would they distribute those profits to the public? Personal accountability FTW!  Rule Number One: If it's too good to be true, it probably is (Source: Cartoonist Group) At the very least, those who would try their hand at investments could do a dry run and see how good they are at it - one thing's for sure, I won't be diving into football punting in real life. $361.25/$500 and falling... $100 on Man Utd to beat Bolton (at 1.17) - It's about time. Next: Midmidterm

|

|||||||

Copyright © 2006-2025 GLYS. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||