|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

TCHS 4O 2000 [4o's nonsense] alvinny [2] - csq - edchong jenming - joseph - law meepok - mingqi - pea pengkian [2] - qwergopot - woof xinghao - zhengyu HCJC 01S60 [understated sixzero] andy - edwin - jack jiaqi - peter - rex serena SAF 21SA khenghui - jiaming - jinrui [2] ritchie - vicknesh - zhenhao Others Lwei [2] - shaowei - website links - Alien Loves Predator BloggerSG Cute Overload! Cyanide and Happiness Daily Bunny Hamleto Hattrick Magic: The Gathering The Onion The Order of the Stick Perry Bible Fellowship PvP Online Soccernet Sluggy Freelance The Students' Sketchpad Talk Rock Talking Cock.com Tom the Dancing Bug Wikipedia Wulffmorgenthaler |

|

bert's blog v1.21 Powered by glolg Programmed with Perl 5.6.1 on Apache/1.3.27 (Red Hat Linux) best viewed at 1024 x 768 resolution on Internet Explorer 6.0+ or Mozilla Firefox 1.5+ entry views: 2555 today's page views: 906 (23 mobile) all-time page views: 3732950 most viewed entry: 18739 views most commented entry: 14 comments number of entries: 1256 page created Fri Mar 6, 2026 15:32:59 |

|

- tagcloud - academics [70] art [8] changelog [49] current events [36] cute stuff [12] gaming [11] music [8] outings [16] philosophy [10] poetry [4] programming [15] rants [5] reviews [8] sport [37] travel [19] work [3] miscellaneous [75] |

|

- category tags - academics art changelog current events cute stuff gaming miscellaneous music outings philosophy poetry programming rants reviews sport travel work tags in total: 386 |

| ||

|

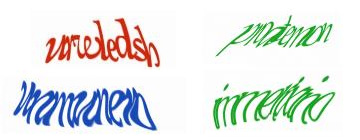

- academics - It's the final day of the Premier League, and the current punting standings are: 3207 seeds for Mr. Ham! (both from 3100 seeds wagered) Mr. Ham: Useless human is going to lose after I gave him a thousand-seed headstart! Nyeah nyeah! Me: I'm not certain that FAKEBERT is human... Mr. Ham: I'm not letting that stand in the way of my declaring hamster superiority. Final wager: What better way than to finish with a flourish by having hams share the spoils? Tottenham to draw Fulham! (at 4.25) FAKEBERT: I'll take Manchester City to beat Queen's Park Rangers (at 1.10) Me: With that bit of business out of the way, may I draw the focus back to one of my part-time diversions, the study of machine recognition in general and CAPTCHA solving in particular, which I have given attention to not too long ago. However, while that more applicative-based attempt was centered on a relatively simple target, it is time to widen our horizons; and what better way than to set the Google CAPTCHA in our sights? Less than half a year ago, Stanford researchers reported that they were unable to break a single of Google's CAPTCHAs, yet were able to crack 13 out of 15 other types of CAPTCHAs with accuracies that are usable in practice (mostly over 25%) [see academic paper] It should be noted that a researcher with links to a local lab had reported [see paper] the ability to solve 68% of Google's CAPTCHAs back in mid-2011. However, this success may be tempered by the revelation in Section 3 that they initially divided the CAPTCHAs into "user-unfriendly" and "usable" classes, and developed (and presumably evaluated) their method on only the easier "usable" class, using 100 samples. Clearly, the conclusions may not then be applicable to the wider set of all CAPTCHAs, which is what users actually face. To this end, I requested Mr. Robo to collect the data for an independent experiment. Mr. Robo: Aye, aye. I have obtained the sum of 2000 samples from the former Google Accounts UnlockCaptcha page back in February. They've since closed this source of CAPTCHAs, but it should be valid for our purposes. Me: Nice work, Mr. Robo. I'll see you get that promotion to code bunny soon. Well, the obvious next step is to create a ground truth for these CAPTCHAs. And how might we go about that? *Looks at Mr. Robo, together with Mr. Ham* Mr. Robo: Wai... wait a minute! It's written in my contract that I don't have to do data entry! Esquire Pants: *appears out of nowhere and inspects contract* Looks legit to me. *Looks at Mr. Ham* *Mr. Ham stares back blankly, slowly keels over* Mr. Robo: My word! Is he dead?! Me: *pokes the motionless Mr. Ham with a chopstick* He's certainly getting better at it, he's even getting the turning black part right. Oh well, I suppose it can't be helped... *Hours later* Me: That's... that's all two thousand CAPTCHAs sol... solved. I... I don't want to... look... at another CAPTCHA for the rest of... my life. Mr. Robo: Erm, but how would you know how confident you should be about your answers? Me: Tha.. that's right... so... how do... we... resolve th... this? Mr. Robo: Um, there's intra-rater reliability. Which basically means you got to do it all over again, and see how different the results are.  My reaction to this realisation (Source: gifbin.com) *More hours later* Me: *crawling up from under the desk* D... done. Mr. Robo: But wait, what are you gonna do if they still don't agree? You had better do it a third time so that you can apply a majority voting rule for the disputed cases. Me: I... will... personally... strangle... anybody... who... suggests... that... Mr. Robo: Um. Okay. Never mind then. Let me analyse the results first. *codes away* Lookie what we have here, only 143 of the 2000 answers disagree with each other, giving a 92.85% intra-rater reliability for you. A 2010 study, again by Stanford, found 92.1% agreement by two out of three humans offering their services under Amazon's Mechanical Turk framework, and only 66.72% unanimous agreement by all three, for Google's CAPTCHAs, to give some perspective. Bottomline is, solving state-of-the-art CAPTCHAs isn't that easy, and may even have some correlation with general intelligence - the paper noted that solving speed is weakly correlated with educational level, 9.6 seconds on average for those with no formal education and 7.64 seconds for those with doctorates, at least for image CAPTCHAs. Some have even declared CAPTCHAs dead (back in 2008), and even the better ones are often regarded as near-unreadable (see comments here, and feedback like this, which has a good point about international users and Latin letters), with an obvious solution being to re-engineer sites such that the onus of stopping bots falls on the server side (e.g. using spam filters), rather than the client. It should also be noted that the results obtained from our dataset might not be directly comparable with prior research (again!), since Google likely updates their generation algorithm every now and then. For example, from our 2000-sample dataset, the average length of a CAPTCHA is 8.98 characters, with a median of 8, a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 11; this is a departure from the paper covered previously, which states that the string lengths vary between 5 and 8 characters only, at least for the "usable" class.  In fact, Google CAPTCHAs of length 7 or less were extremely rare in our dataset, with the vast majority being of length 8 to 10. Google might well have decided to bolster security by increasing length, since it is evident that each additional character should reduce machine solvability by at least (1-x), where x is the average recognition rate for each individual character, assuming they demand perfect answers. As it turns out, CAPTCHAs for which there was intra-rater disagreement tended to be slightly longer, but not significantly. The trouble, as I will show later, lies elsewhere. Me: The problem remains. How do we proceed? Mr. Robo: Well, it would be best to collect some more data first, so we don't depend on answers from just you. Do you have any favours you can call in? Me: I think Mr. Ham is the go-to guy for that. *looks over* Nope, he's still dead. Mr. Robo: Oh, he was up and about munching on some peanuts just now. Me: Forget it, I'll put in a plea to my friends, especially those who are currently pursuing or may in the future pursue further studies, since they are more likely to be sympathetic. I can't quite ask them to go through all 2000, so please select a hundred examples for me, split evenly between my intra-rater agreement and disagreement classes. *A couple of days pass* Me: Alright, it seems like I got three responses. So how did they do? Mr. Robo: More detailed results are available, but I will give a summary. Of the 50 disagreement images out of the 100, 13 (26%) of them were agreed upon by all three volunteers - for these, I suspect that the disagreement was more due to fatigue and other factors on your part, and not because of any inherent indecipherability of the CAPTCHA itself. As a whole, the agreement class did still obtain much better consensus among everyone, as is to be expected. Fully 66% of the images in that class were agreed upon by all four participants, as opposed to 26% for the disagreement class, picking either of your answers as valid for that class. The distribution is as follows:  It therefore does seem that your intra-rater disagreement is a pretty good predictor of how difficult the CAPTCHA actually is, and the 60-odd percent concurrence tentatively supports the Stanford findings. Four of the disagreement CAPTCHAs (8%) received a different solution each of the five times they were evaluated, and here they are:  urwledsh - vawledsh - urveledsh - uawledsh - vorveldsh pnoatemon - proatemon - prxtemon - pnatemon - pratrnon immelxino - immelixino - immerxino - immeixino - immerxno unmvanevo - unmvnero - uraminero - uamwnew - uvaraunevo It therefore seems near-certain that some CAPTCHAs are, indeed, basically unsolvable, or more technically, that their deformation has destroyed critical information. From observation, these "bad" CAPTCHAs are especially wavy and squashed, making it difficult to tell loopy (e.g. m,w) or thin-type characters (e.g. i,l) apart. Some tangential statistics: Of the 50 agreement CAPTCHAs, you have an average of 84.67% agreement with the volunteers (92%, 86% and 76% respectively). Volunteers 1 and 2 agreed 84% of the time, but their agreement with Volunteer 3 was only about 70% each. On to the speed of solving - the volunteers were told to solve the CAPTCHAs as-per-normal, as if they were confronted by them in the normal course of web surfing. Since they could well have taken breaks in between (which you can doubtless understand), I report the median time taken. Note that since individual times were recorded to the second, and internet speeds may have had an effect, this is a very rough estimate:  It is observed that Volunteer 2 [Median time: 4s/Mean time disregarding outliers: 4.94s] was the fastest, followed by Volunteer 3 [7s/8.28s], while Volunteer 1 took slightly longer [8s/8.36s] (but also achieved the highest agreement with yours truly); the average of about 7.2s is slightly faster than the 7.64s reported for solvers with a doctorate, even considering the skewed nature of the 100-image dataset, which contains harder CAPTCHAs than might be expected. Somewhat surprising is that the collated results do not show more time being spent on the trickier disagreement CAPTCHAs than the more straightforward agreement ones. I'm sure you can cook up several hypotheses for this:  Me: Enough with this, anything actually useful? Mr. Robo: About that, one realisation is that the strings are far from truly random - some substrings, in particular, cropped up every so often: "ssess" about 22 times, for example, although that might be expected only in no more than one in a million CAPTCHAs were the characters really selected randomly; Even "glys" came up about five times! We can very quickly confirm this through, you guessed it, frequency analysis, which despite some errors should give the big picture (17967 characters from the 2000-CAPTCHA data, Concise Oxford data from Wikipedia):  It seems safe to say that the CAPTCHAs were generated from a distribution similar to an English corpus. Indeed, this may well aid CAPTCHA recognition for humans - instead of having to identify each character on its own merits, neighbouring characters might well be used for difficult characters or substrings, if subwords are incorporated, a feature which many other CAPTCHA implementations may have missed. Indeed, an update on the baboon word recognition study mentions that they may well be making their decisions based on bigrams (letter-pairs) or trigrams (or not)! Does the CAPTCHA data in fact conform to common bigram distributions as well?

As it happens, not quite. For example, "th", which is the most common English bigram by some distance, is not represented within the top 30 CAPTCHA bigrams (it comes 86th); however, there remains quite a bit of overlap, with 23 of the 39 most common English bigrams found within the top 30 CAPTCHA bigrams, which again suggests the use of an English-like corpus. Alright, I think that's enough for today. Me: Hey, you haven't even began to crack the CAPTCHAs proper! Mr. Robo: Patience, Hamopolis wasn't built in a day. Next: Meaningful Hiatus

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © 2006-2026 GLYS. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||