|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

TCHS 4O 2000 [4o's nonsense] alvinny [2] - csq - edchong jenming - joseph - law meepok - mingqi - pea pengkian [2] - qwergopot - woof xinghao - zhengyu HCJC 01S60 [understated sixzero] andy - edwin - jack jiaqi - peter - rex serena SAF 21SA khenghui - jiaming - jinrui [2] ritchie - vicknesh - zhenhao Others Lwei [2] - shaowei - website links - Alien Loves Predator BloggerSG Cute Overload! Cyanide and Happiness Daily Bunny Hamleto Hattrick Magic: The Gathering The Onion The Order of the Stick Perry Bible Fellowship PvP Online Soccernet Sluggy Freelance The Students' Sketchpad Talk Rock Talking Cock.com Tom the Dancing Bug Wikipedia Wulffmorgenthaler |

|

bert's blog v1.21 Powered by glolg Programmed with Perl 5.6.1 on Apache/1.3.27 (Red Hat Linux) best viewed at 1024 x 768 resolution on Internet Explorer 6.0+ or Mozilla Firefox 1.5+ entry views: 2117 today's page views: 234 (32 mobile) all-time page views: 3385900 most viewed entry: 18739 views most commented entry: 14 comments number of entries: 1226 page created Thu Jun 19, 2025 20:29:05 |

|

- tagcloud - academics [70] art [8] changelog [49] current events [36] cute stuff [12] gaming [11] music [8] outings [16] philosophy [10] poetry [4] programming [15] rants [5] reviews [8] sport [37] travel [19] work [3] miscellaneous [75] |

|

- category tags - academics art changelog current events cute stuff gaming miscellaneous music outings philosophy poetry programming rants reviews sport travel work tags in total: 386 |

| ||

|

- Baron Vladimir Harkonnen "Oil, the Earth, yadda yadda." - various contemporary human leaders Warm-up Exercise But before we get started on the main course: which of these letters, A, B or C, got published by The State's Times?

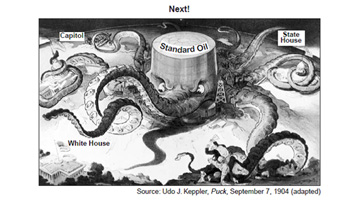

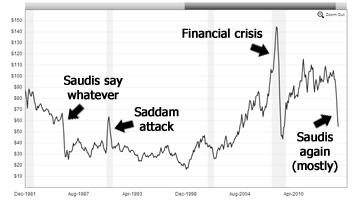

Answer: It was a rhetorical question. Anyhow, the town council in question has just been slapped with an S$800 fine for holding a trade fair without a permit, quite possibly due to the usual hanky-panky over red tape, but whatever lah, huh. But some credit to The State's Times, they did recently publish an alternative viewpoint on the woes of the lower-income segment, though this only came after the writer pointed out that an earlier commentary wound up on the foreign Wall Street Journal only because it had not been accepted by The State's Times, which I suppose is fair enough. And from the "other side", the sued-and-waiting-for-damages-to-be-assigned blogger appears to have thrown in the towel for now, with what was probably at some stage the most "happening" local political hotspot now headed by what could be a farewell post. Then again, with new critical outlets popping up about as quickly as older ones fade away, the overall impact is likely not all that significant. The Prize  (Source: Amazon) Today's review is Daniel Yergin's The Prize, which as it so prominently proclaims on the cover, won the Pulitzer Prize (in 1992). After getting through its near 800 pages of content, I retained two impressions - first, that it was a fairly smooth, and dare I say, light read in terms of tone. Secondly, the overarching story is actually very compressible, though of course it's all the tiny details that hook one in. I compulsively snagged it from the library both due to the ongoing oil price crash (which is currenly just above US$50 a barrel, from hovering about US$100 for several years), and because I vaguely recognized the title from somewhere. On that first point - so why is the price of oil freefalling? First stop would be the major news outlets, who tend to largely attribute it to market forces - Libya's production is up, the USA is working on shale oil, China's weakening economy means lowered demand, etc. Juicier conjectures, involving backroom intrigues and old feuds, tend to be given short shrift, if not skipped over entirely on these reputable sites. For these, you'd have to venture into the deeper bowels of the Internet, where smug wiseguys (like yours truly) serve up their own blends of conspiracy. Saudi Arabia being out to get Iran (religious rivals) and Russia (meddlers in Syria) by battering their revenues is an oft-repeated one, as is surreptitiously sabotaging America's venture into other sources (it's a complicated relationship); the descent from these plausible theories to Freemasonic Illuminati Rothschilds reptilian alien cabals (under Jewish control, it goes without saying) is not very far, so take care not to delve too deep. The disclaimers done with, it has to be admitted that oil prices do have a great impact on our world. We've seen the mad rush to spend fast-depreciating rubles in Russia as Putin tries to maintain control with bold proclamations in this run-up, as well as fuel subsidies being a big issue in neighbouring countries long before this. But why all the concern? The Age Of Oil  Our modern-day moais. (Source: opinion-maker.net) Fine, fine, that was a bloody dumb question. Because oil is essential to about every facet of the modern world. Reading this post on a computer? You're consuming electricity - okay, coal and natural gas are king here, with oil only contributing about 5%. But the food that one eats? The goods that one buys? The jobs and homes that one goes to and returns from, each and every day? What do the motorcycles, cars, vans, buses, lorries, eighteen-wheeler trucks, locomotives and airplanes all burn, without going into the heavy machinery employed in factories and industries of all types? Petrol, diesel, kerosene... i.e., oil. Seen from this angle, it is evident how Yergin's book, which some have described as history told from the lens of oil, makes sense. Indeed, it might be a more ambitious undertaking to explain modern history without considering oil. Basically, there are few nations today who can conceivably remain functional for long without it - people wouldn't be able to get to their workplaces, nor new stock to stores, though many densely-populated cities would probably be in chaos long before unemployment becomes an issue, as grain rots in far-flung warehouses while starvation sets in. Sure, it was not always like that. We're not that far removed from the time when automobiles and steam engines became prevalent, after all - barely a century for the former, a couple hundred years for the latter. Then, most lived and worked rather closer to the land, and urban areas were limited by the fertility of the immediately surrounding area, among other factors. Oil and gas were, even when so abundant as to be burning its way to the surface, mere curiosities. But things can change, and when they do, they can change very quickly indeed. Let us then start from the beginning, which Yergin set as the 1850s. Then, a distinguished Yale professor of chemistry named Benjamin Silliman, Jr., desiring to supplement his meagre academic income (some things don't change), undertook to analyze a newfangled substance called "rock oil", named for its origin and initially marketed not as a fuel, but as patent medicine. Silliman confirmed that rock oil was very suited for use as lamp illuminant, and moreover had the sense to withold his full report until he got paid his US$526.08. Encouraged, the investors undertook to drill for the oil (itself an innovation), and after many setbacks and unspoken ridicule, their representative the self-styled "Colonel" E. L. Drake hit paydirt in Pennsylvania, just before funding ran out (this would be a recurring theme throughout the rest of the book) It turned out that people liked being able to see at night for cheap, and a rush for the "black gold" ensued, which ended with this first oil bubble bursting around 1866. An oil exchange opened several years later, but this period would be marked by the rise of one of the great American monopolies - John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil. This he achieved through ruthlessness and organizational genius, as the cautious and methodical Rockefeller pieced his empire together on efficiency and economies of scale (and some strong-arming) Evidently, charisma isn't always needed to succeed in business, as one of Rockefeller's favourite ditties went: The more he saw the less he spoke, The less he spoke, the more he heard, Why aren't we all like that old bird? He was also a bit of a cheapskate, charging his acquaintances for room and board after inviting them to stay over, a tradition kept up by later oilman J. P. Getty, who installed a payphone in his guesthouse - but we're getting ahead of ourselves here. Other countries weren't too far behind the curve, with Russia close behind as the Nobels (of Nobel Prize fame) and Rothschilds (of high finance fame) got a foothold in Baku (home of the pillars of flame that the Zoroastrians worshipped) and began exporting to Europe, even as the original Pennsylvanian wells began to run dry. Welcome to Singapore  Jurong Island, today. (Source: businesstimes.com.sg) We jump now, about the year 1890, halfway around the world to a very familiar sunny island set in the sea. It is widely known that Singapore is a major oil refining hub, with operations now centered around Jurong Island, but it is also a fact that we played a substantial role in the regional oil trade, over a century ago. [N.B. While we're on energy, the incumbent party has gotten flak for U-turning on nuclear power within the short span of a few years, with more and more signs pointing to us eventually taking up the option. There are obvious arguments against building a reactor here, but then given that we've committed to the casino route, what's one more big incumbent gamble?] The 1867 opening of the Suez Canal had cut the distance to the Far East considerably, and Singapore was well-positioned to benefit from the concurrent increase in shipping volume. Discovering that Orientals liked night vision as much as Occidentals, a son of a Baghdadi seashell vendor managed first to convince the Suez operators that his new oil tankers were safe, and then was smart enough to recognize that Far Eastern buyers were after useful tin cans as much as the oil they contained. Commissioning batches of red cans to compete against Standard Oil's blue (echoing the later Coke-Pepsi wars and various sporting rivalries), the Rothschilds-backed Shell soon made large inroads into the Asian market. The third and last major geographical discovery of the 19th century, after the earlier strikes in the USA and Russia, was also close to home. Recall that much of Southeast Asia had been divided into British and Dutch spheres of influence (in some part to clarify the ownership of Singapore) not long ago, and it was in the Dutch East Indies (i.e. Indonesia) that a tobacco company manager discovered oil in northeast Sumatra about 1880 (the natives were using the mineral wax to light torches). Ten years later, Royal Dutch was launched, with the support of the King of the Netherlands himself. [N.B. If The Prize is to be faulted, it would be for the wholesale omission of the discoveries in Brunei, as far as I could discern (though it could be argued that their remaining reserves are actually not that notable). For a fuller telling of Shell man T. G. Cochrane's famous "I smell oil!" exclamation, and the subsequent development (or lack thereof) of Brunei, and a look behind our close ties (extending to a currency union), I highly recommend Bartholomew's The Richest Man in the World, which came out about the same time as The Prize.] A Matter Of Trust  Political cartooning, a refined art. (Source: 21stcenturylearning.sharepoint.com) So, to recap the first fifty years or so - Standard Oil remained the granddaddy of oil companies, with their stranglehold on refining and distribution (though not prospecting and extraction, which they regarded as iffy), crushing opposition with tactics ranging from selective price cutting (sound familiar?) and buyouts, to outright violence. Shell and Royal Dutch were their major competitors outside America, but not quite at a level to take Standard head-on. But the new century would move swiftly. By 1904, the journalist Ida Tarbell had compiled her magnum opus, exposing Standard Oil's monopolistic excesses. Backed by public sentiment, President Theodore Roosevelt's administration got Standard Oil on the charge of restraint of trade, and Standard was soon no more, broken up into dozens of successor companies, which included many to-be present-day giants such as ExxonMobil, Chevron and Aramco. If the intention of the breakup was to increase competition, however, results were mixed at best, as the "Standard babies" came equipped with their own territories and shared brand names, making contentions hard. Not that they fought that fiercely with Shell and Royal Dutch either, with their relationships perhaps best described as a friendly rivalry, the usual stable state of oligopoly (now still expressed in petrol pump pricings, if hard to prove) A few more things happened about this time - some Standard scientists improved the cracking process greatly, increasing gasoline (petrol) yield from crude, while an English speculator won a concession from the Shah of Persia (present-day Iran), and after seven barren years, struck oil at Masjid-i-Suleiman, home to another temple with a natural eternal flame (you'd think the explorers would have gotten the hint by now). Yes, for all the hoopla over Middle Eastern oil nowadays, they were latecomers (moreover, America remains the largest oil producer overall today, but is also the biggest net importer) These foreign concerns would prove troublesome - while American finds were hardly organized, with a wild west atmosphere pervading the new oil boomtowns in Texas, Oklahoma and California, it would be worse elsewhere. Early arrivals to the Dutch East Indies were afflicted by all manner of tropical disease; D' Arcy soon found that his Persian concession was in practice controlled by nomadic desert tribes, and got extorted left and right; and Russia, ah, Russia. The big revolution wasn't far off, and Baku happened to be a Bolshevik hotbed, with the local Tartars and Armenians intent on slaughtering each other. Very bad for business. As it happened, the inept Imperial Russian navy was soundly beaten by the Japanese in the Battle of Tsushima (1904), which together with the rise of German ambitions, contributed to the sense of urgency at the British Admiralty on preserving their naval supremacy. On this, both the First Sea Lord John Arbuthnot Fisher and a certain new up-and-comer Winston Churchill were in agreement, and they championed the conversion of the fleet to oil from coal, to achieve greater speeds while reducing the need for manual stokers. There was a complication in that while Britain had ample supplies of good Welsh coal, it had no known oil reserves then, and Shell (headed by an Anglophile) had by then become the junior partner in the merged Royal Dutch Shell (today's "Shell"). This dependance on a mostly-foreign entity for strategic material was intolerable, despite Shell's protests, and Her Majesty's Government took a majority interest in their loyal subject D' Arcy's struggling Anglo-Persian company. Birth Of The Political-Military Complex  That'll be twenty francs, monsieur. (Source: thisdayinalternatehistory.blogspot.sg) It was about time for the First World War, and it is probably little remembered that French first responders rushed to the front in Parisian taxicabs (who charged by the meter), after their railways had been disrupted. Britain's upgraded fleet was enough to keep Germany's above-water vessels (still on coal) holed up at port, aviation tactics evolved at an astonishing pace, and the first tanks made their appearance. That said, oil was probably not that critical to the military as of yet. Coal-fired warships weren't completely outclassed, tanks and automobiles were notoriously unreliable (Eisenhower's 1919 American road trip took almost two months), and horses often proved more than enough. However, it was still regarded as significant enough for Germany's Ottoman allies to race them for control of the Persian and Baku oil fields, which were thus preemptively destroyed by British forces. Germany's diesel-powered submarines did make the British navy sweat some, but their doctrine of unrestricted warfare brought the Americans into the war, so they lost. The Americans, English and French were suddenly closer friends from their shared experiences, and by 1928 had agreed to share oil production in much of the Middle East (with some later disputes), under the Red Line Agreement. As Germany chafed under its onerous peace treaty obligations, the victorious Allies got their quest for more oil underway as demand exploded with the rise of the automobile, and some of the usual cloak-and-dagger schemes ensued (the confirmed ones of which include Lawrence of Arabia inciting an Arab revolt against the Ottomans), that tended to leave rulers friendly to their interests on the thrones of hastily-created states. Mexico and Venezuela came online, as did the newly-Communist Russia after awhile. There was a brief panic in the early 1930s as huge discoveries in and around Texas sunk the price of oil to below production costs, which forced the American government to set quotas (which, as we will see, would become something of a standard practice), not helped by the Great Depression. The price remained around a dollar a barrel for the rest of the decade despite efforts from the big boys to drive it up, in part due to non-cooperation from their Russian competitors. Of the major inter-war happenings, though, one event stood far above the rest - the entry of Saudi Arabia to The Game. The House of Saud  That'll be... ah, who cares how much it was, my raisin? (Source: strangecosmos.com) [Longer video of the effective courtship ritual] Nowadays, when one hears about Arabian sheikhs, one impression springs instantly to mind - ridiculously, filthily rich. It was hardly always like that, though. In the 1930s, the founder of the current Saud dynasty was a mere dispossessed desert warlord, albeit an imposing one, who could carry his entire national treasury in the saddlebags of his camel. Ibn Saud had started his reconquest in the name of Wahabism, but despite his victories on the battlefield, he was faced with a pressing problem - money. The Great Depression had slowed the flow of pilgrims to the holy city of Mecca, previously his major source of income, and the salaries of his civil servants were already unpaid for months, to say nothing of the developmental plans for his new kingdom. Despite that, his foremost desire was not for oil or even money, but something situationally more precious: water. In this, he would be disappointed, but he made the acquaintance of Harry Philby (the father of later Soviet spy Kim) due to the venture, who in turn informed him of the possibility of cold, hard cash for granting concessions. With oil having just been found in neighbouring Bahrain, there could be interest. Kuwait was also desperate after the Japanese invention of cultured pearls had destroyed its diving industry, and within a few short years, Socal (Standard Oil of California), British Petroleum and Gulf Oil had set up subsidiaries to prospect for oil in the desert. Initial pickings were slim, but by 1938, huge discoveries had been made in both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Unfortunately, with the onset of the Second World War and diplomatic approaches made by the Axis powers (including a gift of classic samurai armour), these wells were plugged. About a year ago, the Japanese had clashed with Chinese forces in the Marco Polo Bridge incident, and it was clear that the world was spiralling towards another war. What was also clear, at least to commanders with two functioning brain cells, was that bravery and small arms, while merely inadequate a few decades ago, were by now next to useless without the supporting machinery - and by association, oil. Much of the fighting, then, was tasked towards securing this vital resource. The Nazis made for the Caucasus as soon as they were able to, with their objective the Baku oil fields, while Japan were only too aware of how vulnerable they were to suspended oil imports. Their target was naturally then Southeast Asia, but the only realistic way to go about this without interference was to cripple the American fleet based at Pearl Harbour. This they achieved in spectacular fashion (but without exploding the oil tanks there, for some reason), but it also meant that the Americans had to enter the fray against them, proving once more that nobody learns from history. Back in Russia, old reliable General Winter repelled the previously-unstoppable Nazis, who never got the foothold they wanted in the Caucasus. In the Pacific, Japan did take over Indonesian refineries and got them going... only to find that they couldn't get the oil back to the home islands, with Allied air and submarine superiority wasting most of their shipping. The Axis powers were soon reduced to trying to produce synthetic substitutes, with Japanese kids conscripted to scrabble for pine roots to that end (it turned out that the pine oil produced was pretty useless as fuel). Even the Desert Fox, Rommel himself, was grounded due to a lack of petrol. The Allies were confident enough that the tide had turned that they resumed their explorations in the Middle East before the formal end of the war, with British-Saudi relations helped by the timely provision of US$2 million worth of gold coins (likely, as previously, graced with the profile of a male monarch instead of Queen Victoria, out of cultural sensitivities). At this point, though, the entire Arabian peninsula was useful, but hardly critical - its production was barely five percent of the world total, compared to over 60% for the United States. Increasingly sophisticated studies would, however, indicate that the center of gravity of oil lay not within the States, but in the Middle East, the Cradle of Civilization; the birthplace of so many religions, it was perhaps indeed a land blessed by God. A New World Order  The most powerful flag. (Source: commons.wikimedia.org) With the world at peace once more (ignoring the Cold War), it was again time for the victors to divvy up the spoils. By 1951, American and British-led firms had split most of the known Arabian fields between themselves, having resisted a Soviet attempt to muscle in on Iran. There were a few lawsuits, but eventually all the loose ends were tied up, and oil execs were sitting back and dreaming about huge and easy profits... Then, Arabian nationalism happened. Or, it had always been present in some form, but the various rulers and petty chiefs soon recognized that the stakes were far higher than before. While the Saudis might have been happy to sign off on a concession for their entire landmass for a mere million bucks just two decades ago, they and their fellows quickly reasoned that they deserved rather more of the profits, as D' Arcy's nomadic adversaries did. It was their land, darn it, and they wanted the cheese. Obviously, the Western oil companies didn't see it this way, and pointed out that they had invested plenty in the infrastructure, and before that in exploration, when there had been a good chance of no returns at all. Of course, being officially the good guys, the Ameribrits couldn't openly swoop in and "arrange" matters, and things came to a head in April 1951 when the new Iranian Prime Minister announced that the Anglo-Iranian company was henceforth nationalized. Now, this was too much, and the good guys were ready to kick some ass. Mohammad Mosaddegh was freely democratically elected, but then, only the humans voted - won't somebody think of the oil? They bided their time, and two years later put Operation Boot into action, ousting Mosaddegh and placing the former Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (CIA codename "Boy Scout") in power, as an absolute monarch. But hey, he enfranchised the oil! Could you ask for more? This was against the backdrop of constant tension over the formation of Israel in 1948, the implementation of which was probably another British muck-up, but that's a whole other story. Nasser did call their bluff over the Suez canal after a loan for the Aswan Dam was withdrawn, wresting control back to Egypt, but overall the Westerners had it their way. Major producers chipped in with embargoes against the British and French in the wake of their failed Suez operation, but Israel survived the general hostility and would much later win two short and decisive wars, partly due to their foes not quite being all that great friends with each other either, a situation that persists to this day. Before those tests, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) had been formed in 1960, after a disastrous unilateral price cut of seven percent by Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon/Esso), which remained dominant in the American domestic market. Other companies followed suit, wreaking havoc on the budgets of their host nations, who were furious enough to band together as OPEC. Despite the potential, OPEC was actually not all that influential early on. While they had a common interest in countering the private oil companies' power, they were also direct competitors, whose aims did not always align. For example, many large Arab producers did swing the "oil weapon" against countries friendly to Israel during the Six-Day War of 1967, but their united front soon disintegrated as the states figured that while they were brothers of the faith, cash was nice too. Still, it was true that the world was getting more and more dependant on Middle Eastern production, and while new finds were made in Nigeria, Indonesia and even Alaska, the Sixties saw OPEC countries claim a larger and larger share of global production. With this new-found importance came boldness, and Arabian leaders pressed their claim for more of the pie. Gaddafi came to power on the back of this dissatisfaction in 1969, and within a year the Shah of Iran had destroyed the old fifty-fifty profit-sharing compact that had stood for decades, getting 55%. OPEC was flexing its muscles. The Final Weapon  Well, what else? (Source: finalfantasy.wikia.com) We are now entering the last twenty years of The Prize's chronology (it was published in 1991), which more or less coincides with OPEC's ascendancy. In 1940, its key members were but minor players. By 1973, they - and Saudi Arabia in particular - had become the supplier of last resort for the entire world. Americans, addicted to abundant gasoline and the automobile culture, were not about to give up their lifestyles, and the Saudis were the only dealers in town. 1973 was also coincidentally the year of the Yom Kippur War, where the Arab kind-of-coalition (more of an oilition, but yeah) figured that if they couldn't beat the Jews in a straight-up fight as learnt from bitter experience, they would cunningly hit them while they were unprepared. To this end, Egyptian forces cunningly attacked on the Number One Jewish Holy Day, and crossed much of the Sinai Peninsula unopposed. This sneaky stratagem however neglected that, while Yom Kippur did mean that Israeli forces would be fasting and praying, it also meant that they would be all at home and ready for mobilization, and that the roads would be totally empty, and ideal for military usage. It was very sad, and within a fortnight the Israelis were advancing on Cairo and Damascus respectively, despite Soviet support for the Arabs. It was looking to be an extremely embarassing repeat of 1967, when the aggressors wound up losing territory to Israel (including the Sinai that they Egyptians had just so cunningly crossed), but there was a small difference this time - the oil weapon had finally matured. Basically, you can't blackmail somebody with something that he still has, and not long ago, the USA still had spare oil. That was no longer true. In fact, a month before the war itself, a word from the Saudi king had been enough to draw a televised statement from U.S. officials that their interests "were not synonymous" with those of Israel. Indeed, Israel was in a bit of a spot for awhile, as the Americans were loathe to draw an actual embargo by resupplying them; they eventually resorted to unmarked air transports and night landings, which fooled no-one. So, the embargo began, with a twist - other than subjecting the U.S. to the steepest cuts, which was expected, the Arabian members of OPEC further resolved to cut overall production by five percent a month, until their objectives were met. This was because, had the embargo been simply targeted, the U.S. could have just turned around and bought the oil second-hand. Under wholesale cuts, however, they would be well and truly squeezed. It was no longer about the money - the American dollar had just been devalued twice, and anyway they already had more of it than they could fling at comely belly dancers. It was about giving the infidels the Middleeastern Finger. This probably helped the Egyptians get a ceasefire with most of their face intact, and the OPEC states quickly realised that demand for oil was heavily inelastic. In short, if they stuck to their guns, they could actually earn more by making fewer barrels available, as the reduction in quantity would be more than made up by the rise in price. Gasoline pump prices rose by 40% in months in the States, with other advanced economies similarly affected. That said, the big oil companies retained some power - although the Arabians were trying (with some degree of success) to split the Westerners by assigning each country an export status (curiously, the British were given the top rank of "friendly", possibly to drive a wedge between them and the U.S.?), the companies still controlled the distribution, and could jiggle the numbers a bit, especially with non-Arab oil. Moreover, some of the Arab states were also in the strange position of denying fuel to the U.S. Sixth Fleet, which was supposed to be protecting them. Certainly, the threatened five-percent-per-month cutback could not go on for long before the Americans became really pissed, and in any case their main objectives - of displaying their might, and preventing the Israelis from stomping all over Egypt - had been achieved. Realistically, Israel itself wasn't going away just yet, so with pride satiated, talk turned back to moolah. OPEC suggested prices of up to US$23 a barrel, while the Saudis professed to be content with "just" US$8, compared to pre-war prices of under US$3. In a way, then, Israel won the battles, but OPEC won the war. If the Arab oil producers had been filthy rich before, they were now absolutely, mindbogglingly, incredibly frickin' rich. They bought all manner of goods, from advanced weaponry to luxury extravagances. Datsuns replaced camels among the Bedouins. Gleaming skyscrapers sprung up in the sands. One by one, the old concessions were overturned, and the middlemen oil companies were increasingly bypassed. Today And Tomorrow  Crude oil prices, from the 1980s (Source: macrotrends.net) The Prize does not end just yet, with about a decade more to run. The Camp David accords of 1978 seemed to promise some modicum of peace for the region, but not for long as the Shah of Iran was overthrown the next year, leading to the Saudis (opportunistically?) cutting production, and then the Iraqis attempting to take advantage by declaring war on Iran. Meanwhile, OPEC's supremacy was waning, if slightly. Their share of the world market had decreased from over two-thirds in 1977 to less than half in 1982, as new North Sea oil was drilled, and the Soviets began overcoming their aversion to trading with capitalist pigs. The oil industry as a whole was irreversibly shifting from the old integrated model, where companies maintained proprietary production pipelines from the ground to the end-user, to a more open market-based approach. Gasoline futures appeared on the New York Mercantile Exchange in 1981, and price fixing became less straightforward (though, as we have just seen, is still wholly possible) The Saudis had been playing the role of straight man for some time, adjusting its own output to cater for other, less responsible parties' eccentricities, but by 1985 they had decided that enough was enough - they were not about to dumbly stick to their quotas, if even their OPEC buddies were cheating them by overproducing. And so, as they would repeat closely almost exactly thirty years later (i.e. today), the Saudis said to heck with all of you - I'm gonna pump my ten million barrels a day, you lot can do whatever you want, I don't care. Supply went through the roof, and prices predictably tanked. Consumers were elated, fellow producers less so, and this indirectly led to a cash-strapped Iraq invading Kuwait in 1990, spiking the price again... which is where The Prize finally concludes. In this 2009 edition, the author has added a short eleven-page epilogue, covering the outcome of that war, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and 9/11 among other events. It was noted that the Bush administration's Iraqi adventure achieved little, least of all the discovery of any weapons of mass destruction, or even democracy to the region (well, now that's a bit rich) Other than that, he brings up four main points - the rise of national oil companies (such as Malaysia's Petronas), "peak oil", environmental considerations and energy security (i.e. renewable energy). Of these, the last three go hand-in-hand, and are often combined into the utopian pledge: oil is limited and dirty, so we'd better support clean and unlimited sources. Now, even experts are split over whether we're running out of oil, but it's pretty safe to say that the "running out" part is highly dependant on "how much consumers are willing to pay". US$300? Sure, we'll work all the tar sands we can find. US$3? Sorry, the world's run out of oil. Anyway, renewables are apparently contributing near 20% of current world usage, which seems a fair start - not that the prize is gonna lose its luster anytime soon... Next: Meditations On Value

Trackback by nike sko hvid

|

|||||||||||

Copyright © 2006-2025 GLYS. All Rights Reserved. |

|||||||||||