|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

TCHS 4O 2000 [4o's nonsense] alvinny [2] - csq - edchong jenming - joseph - law meepok - mingqi - pea pengkian [2] - qwergopot - woof xinghao - zhengyu HCJC 01S60 [understated sixzero] andy - edwin - jack jiaqi - peter - rex serena SAF 21SA khenghui - jiaming - jinrui [2] ritchie - vicknesh - zhenhao Others Lwei [2] - shaowei - website links - Alien Loves Predator BloggerSG Cute Overload! Cyanide and Happiness Daily Bunny Hamleto Hattrick Magic: The Gathering The Onion The Order of the Stick Perry Bible Fellowship PvP Online Soccernet Sluggy Freelance The Students' Sketchpad Talk Rock Talking Cock.com Tom the Dancing Bug Wikipedia Wulffmorgenthaler |

|

bert's blog v1.21 Powered by glolg Programmed with Perl 5.6.1 on Apache/1.3.27 (Red Hat Linux) best viewed at 1024 x 768 resolution on Internet Explorer 6.0+ or Mozilla Firefox 1.5+ entry views: 2589 today's page views: 823 (49 mobile) all-time page views: 3246293 most viewed entry: 18739 views most commented entry: 14 comments number of entries: 1214 page created Thu Apr 17, 2025 23:03:40 |

|

- tagcloud - academics [70] art [8] changelog [49] current events [36] cute stuff [12] gaming [11] music [8] outings [16] philosophy [10] poetry [4] programming [15] rants [5] reviews [8] sport [37] travel [19] work [3] miscellaneous [75] |

|

- category tags - academics art changelog current events cute stuff gaming miscellaneous music outings philosophy poetry programming rants reviews sport travel work tags in total: 386 |

| ||

|

- reviews -  [Source: Peninsula Library System] Just as well that I didn't update the blog software to support custom mouseover text after it vanished from Chrome Aura, since it got put back in (with yellow background). Credit probably goes to forum thread skimmers and xkcd readers. It's book review time again, and the subject for today is Taleb's (of The Black Swan and Fooled by Randomness fame) Antifragile. He's certainly not to everyone's taste, with a common reviewer complaint being the perceived smugness dripping through his writing (which too often comes to the fore with direct attacks on those he regards as idiots, a category overrepresented by Nobel-winners in Economics), as well as periodic overexposition; but then, these critics at least read his book, which as he points out within in slamming Sartre (yet another Nobel awardee), is some sort of success. He does admire Mandelbrot (no Nobel), so that's something. The fellow invokes Baal every now and then too [N.B. Taleb's plug for having some religion appears mostly that it admits more uncertainty... but really?] Well, it is true that the main ideas within can largely be communicated a lot more briefly, which I shall attempt. Those desirous of the original text might Google for the title, although of course they should not actually download any PDF copies floating about without first purchasing the book. What's Antifragile? Take a deep breath, here we go...

If you don't read another word, this is probably about half the book - the concept that there exist systems that thrive under unpredictable circumstances, which is supposedly so absolutely original an idea that the author had to coin a whole new word after scouring the entirety of the Oxford English Dictionary and the vocabulary of most Indo-European languages, before devoting a footnote to dismissing the (quite common) observation that resilient seems to fit the bill. Well, a novel word would be easier to trademark if need be... A table follows giving plenty of examples of the fragile-robust-antifragile triad, from which I extract a few of the best:

I'll cover the others in good time, but we may begin with the last row - Taleb observes that nominally middle (and often upper) class employees - junior managers, civil servants, etc - while generally fairly highly and regularly paid, are essentially slaves (remember, much the same opinion as Fussell, who more delicately branded them conservative and guarded) The (good) reasoning here being that such worker drones would be compelled to conform and not adopt any possibly controversial stands, since their salary, promotion prospects, mortgage and vacation rights all hinge on this virtual and perpetual "silence", along with not wearing a necktie of the wrong colour to the office. In contrast, minimum wage guys have far fewer such worries, since if say a security guard is ousted for his unpopular opinions, he can just saunter over to the next mall down the block and resume pocketing his S$5 an hour. Which is, I suppose, why taxi drivers are so often willing to be vocal against the incumbent administration. And, of course, the truly wealthy (and/or connected) just don't give a shit about political correctness. Indeed, much later, Taleb advises to go with a mobster's promise over a government official's, if given the choice, since the former would be nothing if he did not keep his word, while the latter can vanish into his institution. Going by how pledges by the local set have been holding up, I have got to concur. Upside The Downside The Market: If. Before continuing, we really should go a little deeper into this property of "antifragility". Taleb goes into how organics are antifragile (since they self-repair, well, up to a point) while synthetic objects are not (with a few expections; then again, they don't usually go permanently offline after being deprived of oxygen for merely half an hour), but perhaps the most-emphasized feature, returned to many times in the course of the work, is how antifragility is about keeping the upside while cutting the downside (with reference to Stoicism) [N.B. Taleb manages at various points to drift into how he discovered the joys of short high-intensity workouts and deadlifting his maximums of over 330 pounds (150kg), apparently intimidating fellow intellectuals with his beast-mode build, while also dedicating sections to extolling the Paleo diet (with reservations), intermittant fasting, irregular mealtimes, caloric restriction and general broscience. It is only natural to wonder if he might just be a Miscer... (U Aware, Brah?)] Remember, Taleb's background is that of a financial trader. What do we have from that field that dangles the lure of theoretically infinite upside, for a small and capped downside? Yup, option contracts. Charts of this form tend to look very tantalising:  [N.B. For more interactive online graphs, I recently got introduced to Rickshaw; should be a contender when the discontinued Google Chart API backend is updated] How it works is, let's say this Stock X is currently selling for $95. Another trader might offer the option to purchase it at some stated date in the future at a fixed price of $100, but charge $10 for this privilege. It is clear that the downside (the red area above) is limited - no matter what price the stock goes to, the holder of the option will at worst forfeit it (and the $10 that he paid). In contrast, the upside is clearly unbounded - if the price goes up to $200, the holder makes $90 on his initial investment of $110 (since he spent $10 on the option and $100 to purchase the stock), an 82% return! Indeed, the higher the stock price goes, the more he makes, for a potentially unlimited profit. Under antifragility, this behaviour is extended beyond the stock market, to all aspects of life. Surely There's A Catch? - Taleb, On The Irreversibility Of Broken Packages Otherwise, still keeping with the stock market, everybody would be rushing to buy options, and nobody would be selling them, right, if this here "antifragility" were so powerful? Indeed, and the catch is that the actual numbers matter. Here, consider the St. Petersburg paradox, which involves a very simple game (not the card one, though) that meets the definition of antifragility:

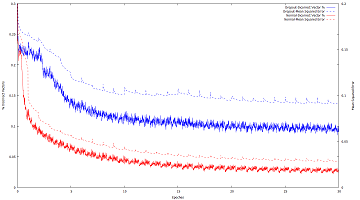

Obviously, the return is exponential - after just five heads in a row, the player would take home $32, ten heads would give $1024, and twenty heads over a million dollars! Indeed, it can be shown that, not only is the maximum upside infinite, even the expected value of this game is infinite too! Antifragility at its purest! However, despite this, it is noted that few people would pay much more than maybe twenty bucks to play the game (though they would of course rationally play it if the cost were one dollar or less). The lesson: the downside, although relatively small - indeed, even if infinitely small relative to the expected upside - matters a whole lot. A few examples: at one point, Taleb advises a bimodal "barbell" investment strategy, where a person doesn't touch 90% of his money, while springing for extremely risky ventures with the remaining 10%, the reasoning being that in this way, he can never lose more than that 10%, while possibly multiplying the 10% wagered many times over if he strikes gold. On the other hand, Taleb reasons, if one simply diversifies everything into medium-risk securities, he might lose it all (say, if the stock market collapsed totally) It sounds cool, sure, but how often does it work? Let's inject some figures now. Assume a starting portfolio of $100000, and also that the available very risky ventures have only a 1% chance of success, but if they do, pay back 100 times on what is put into them (i.e. expected value is unity). A disciple of Taleb follows the master's advice religiously every year, and places 10% of whatever remains in his portfolio into such ultra-risky schemes, and does not touch the rest. A bit of simple math would reveal that he would have a fully 60.5% chance of not having any of his risky investments coming off, over a period of fifty years. In that (not even unlucky) case, since his portfolio shrunk by 10% each year, he would additionally have only about $515 (no, that's not a typo) left in it, down from the original $100000 he started with. And to rub it in, even if he got lucky on his 51st try, he would get only about $5150 (100 times the $51.50 risked) back. Or: supposedly antifragile strategies, with a low enough probability of paying off, can become decidedly fragile; it does not follow from the fact that Martingales are bad, that their inverses are automatically good, regardless of the details. Accepting probable mediocrity has its consequences. Of course, if the risky investments are attractive enough, say they have a 10% chance of the 100-times return, then this type of plan could pay off - but, as emphasized many times in the book, much of the point of antifragility is to hedge against black swan events, where you do not even know what the probability of occurance is, even if one accepts that "black swan" presupposes an outlier for the magnitude of the event. Sure, it could also work if one has special knowledge, e.g. knows that an obscure startup is likely the next Microsoft/Google/Facebook, but in that case any gains would not be due to the bimodal strategy, but to the information. Notably, Taleb brings up the tale of Thales, who cornered the market for wine presses; somehow, he manages to dismiss Aristotle's account that Thales did it because his knowledge of astronomy allowed him to predict a large harvest, and put it all down to the magic of options, ignoring all the poor fellows who put down options in years where the olive crop failed. Returning to the table of examples, biological functional redundancy is hailed, and the author mentions the fact that we have two kidneys, lungs, etc, where we could have done fine with just one of them, as a triumph of antifragility. But if two, why not three? Consider: there may have been many cases where people survived because they had their other kidney to rely on, after one of them failed. However, should we then have a third kidney, following the same logic, in case the first two fail, since the cost of developing another kidney should be a relatively tiny portion of the entire body's budget? And what about all the other vital organs, for which we possess only a single copy? Yet more insurance is not always advisable (especially if what you expect to be covered, isn't) [N.B. Returning to biology, Ridley's explanation in The Red Queen of why there are two genders, born in approximately equal proportion, is more or less this: market equilibrium. If there were too many males, females would be more valuable, and vice versa] It's All In The Numbers - Blaise Pascal The key realisation then is that there is no ideal antifragility independent of context, which can be realised by more careful reading of the many arguments raised - minimum wage workers might be closer to antifragility than mid-level executives, so why aren't people striving to be sweatshop employees instead of app development project managers? This is not to say that the concept of antifragility is piffle, as our Minister for the Environment might finally have realised, just that it is one thing to know about it, but another thing altogether to gain (or prevent loss) by it. Case in point, while the author routinely blasts competitors for essentially being lucky and then rationalizing reasons for their success, his own track record is decidedly mixed; not unexpectedly, when he started Empirica Capital back in 1999 following the bimodal "likely small losses, possible huge gains" mantra, he discovered that the steady drip of losses takes a toll too. Or, as less philosophical veterans might have repeated: "the market can stay black swan-free longer than you can stay solvent". One can additionally reason that if recognition of antifragility becomes widespread, it would then only be logical to move into more "fragile" strategies, since the risky speculation that antifragile tactics demand would have their prices bid up (as during the height of the dot-com bubble, if maybe for other reasons, when venture capitalists were essentially flinging cash at anything that purported to use the Internet) WE'RE ALL ANTIFRAGILE! We might note here that the barbell strategy is quite often run in real life... by the poor. Hey, what does plonking spare cash on scratch-cards and lotteries sound like? Then again, it could well make sense going by utility theory, since buyers might figure that they are more or less about as badly off whether or not they drop $10 weekly on the pools, so why not? Taleb does anticipate this retort by insisting that "risk taking ain't gambling and optionality ain't lottery tickets", but I imagine that he might be strongly cherry-picking here; in particular, he presents many cases where subjects prospered when their big risks came off and attributes it to antifragility, while giving no attention to all those who slowly went broke when their risks fell through. But I suppose that when that happens, it was gambling to begin with, so it doesn't count. He also tries to put lotteries down as having a known maximum upside, but I struggle to think of too much that will trump a Powerball win in monetary terms, and as we have demonstrated, even an infinite upside may not mean much. A final comment, on Taleb's mistrusting "academic theory" in favour of "tinkering and heuristic". His table is a little unfortunate here, since it is clear that he recognizes that theory is reliable in the hard sciences, converging as it does towards the truth. I do agree that those in the social sciences shouldn't be believed too deeply, if only because what they study is much more complex (and also as obvious answers are often ignored due to being politically unmentionable) More precisely, scientific theories based on (massively repeated and properly isolated) experimental evidence are nearly never wrong, simply incomplete; any errors tend to come from attempts to (over)generalise results, but these mistakes are fixed when the actual figures (or better thought experiments) arrive, while usually having little practical impact before then. As oft-noted in machine learning, interpolation between known instances tends to work (with enough data for the "information frequency" of what is being studied) - it's extrapolation into the unknown that's problematic. A small but more specific detour - some of the most recent advances in artificial neural networks have been in adding noise to the network, either in the neuron activation or their weights. Mindful that the only proof is in the pudding, with some prominent researchers admitting that they could not get it to work, I attempted a uniform dropout of 0.5 on all layers of a convolutional network that operated fine without dropout, and discovered that it stopped converging very quickly. More in-depth reading then led me to realise that the 0.5 dropout is only applied to the final hidden layer(s), and when convolutional layers are dropped out (if at all), at most a figure of 0.9 is used. Oops. After making that correction, though, it seems that yet more tweaking (par for course in the field) might be required:  [Click for larger version] I suppose if one has to force a neurological analogy on this (as was traditional), one could imagine cell replacement - but then instead of a fraction being removed for every example while maintaining their state, it would more accurately be a relatively tiny number of cells being completely destroyed at each iteration. The whole area's very empirick. Finally, it's worthy of note that we may probably be overmedicated, if the story about tonsillectomies in 1930s New York is true - when a group of children was presented to doctors, about half of them were recommended for the procedure... regardless of whether they had been previously determined as not needing it. Or: if you go for enough tests to discover something wrong about yourself, you'll eventually find it, because there's no prize for doing nothing. Some Of What Remains I'll end with a few of the remaining ideas, the first of which is the futility of "teaching birds to fly". The lesson here is that mathematically rigorous theory is not necessarily superior to experience and "knack" - uneducated brokers might not be able to differentiate an equation, but could very well outperform MBAs following supposedly well-founded guidelines on the trading floor. Then again, who expects football players to express the coordinates of the ball in matrix format before kicking it towards goal? In support, Taleb puts the wild success of Jim Simons down to concentrating on reproducing the behaviour of good traders bottom-up without preconceptions, instead of trying to construct a grand theory top-down. It transpires that it is possible to produce "how", while not being able to say "why" it works, which happens to be much of machine learning. The other is the Lindy Effect, or that long-lived works and technologies tend to last longer. For example, a classic text like the Odyssey that has managed to exist for a few thousand years can be expected to be around for quite a bit more, while yesterday's national bestseller is likely to be largely forgotten in the next decade. This seems related to the interesting Doomsday argument, which emphasizes just how significant prior estimates are in probability. Lastly, Taleb advocates reducing the agency problem by forcing those in charge to have "skin in the game", a safeguard that dates back to the Code of Hammurabi: he who builds a house that collapses and kills its occupants shall be put to death. Fat hope, of course. Still, with all the previous counterarguments, Mr. Ham was seriously suggesting penning a riposte (something like Think! in response to Gladwell's - who happens to be a Taleb acquaintance - Blink!) to cash in, especially with Herr Ahm's well-defined documented empirical track record to back him up, before I reminded him that it would dent his street cred. Next: Just Noises

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © 2006-2025 GLYS. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||